Patents are used to protect novel products, processes or other utilitarian subject matter. The term of a Canadian patent is 20 years from the earliest filing date. In order for an invention to be patentable it needs to be novel, and meet several other statutory requirements.

Patentability searches

Patentability searches give us an idea of the current state of the art in the field of your invention. Awareness of any prior art that could pose a threat to the patentability of your invention can help us figure out how best to overcome it.

PATENTABILITY

There are a number of different criteria which an invention must satisfy in order to be found to be patentable. These include the following:

- Must have patentable subject matter;

- Must have utility; and

- Must be novel/unobvious.

A patentability search can determine whether an invention meets these criteria.

The novelty of an invention is set out in one or more “claims” which form the core of every patent application. Claims specifically point out and define the scope of the invention. In drafting a patent application the general goal is to claim as broadly as possible without overlapping previously known inventions or ideas, while at the same time fully describing the essence of the invention. Prior art is the yardstick against which the Patent Office measures the novelty of an invention. In addition to published patents, prior art can be any printed information in books, articles, brochures, as well as general knowledge that was made public before the date of filing of the patent application. Such prior art can render a patent application unpatentable for lack of novelty, or on the basis that the invention is obvious. In terms of a lack of novelty, there are two key terms used to further refer to the status of an invention vis-à-vis the prior art. These are “anticipation” and “obviousness”. “Anticipation” occurs when the elements of a certain claim in a patent or patent application are all described in a single prior art reference – a “dead ringer” reference if you will.

In contrast to anticipation, obviousness renders an invention unpatentable if the invention can be said to be obvious by combining more than one prior art references. The question is whether at the date a patent application is filed an unimaginative skilled technician, in light of general knowledge and the prior art available to the technician at that date, would be led directly and without difficulty to the invention. There is a four-factor test to showing obviousness:

- identify who the “person skilled in the art” is, and identify that person’s common general knowledge;

- determine the inventive concept of the claim in question;

- identify the differences, if any, that exist between matters forming the “state of the art” and the inventive concept of the claim; and

- consider whether the differences would have been obvious to the person skilled in the art or whether they require a degree of inventiveness.

The invention is obvious if no degree of inventiveness is required. There may also be a question as to whether an invention was “obvious to try”. For a finding that an invention was “obvious to try”, someone must convince a judge or the Examiner that, on a balance of probabilities, it was more or less self-evident to try to obtain the invention. This is a high standard to meet, since mere possibility that something might turn up is not enough.

In terms of chronological relevance, there are a couple of key dates and concepts to understand as well in terms of the scope and applicability of various prior art references uncovered in the patentability search. Generally speaking the date at which relevance of a prior art reference is determined is the date of filing of your own patent application. Any patent references or other prior art references which are created or published in advance of your filing date are strictly speaking relevant in the perspective of an assessment of novelty and patentability. Items that are created or published after your filing date strictly speaking and generally will not be relevant.

PATENT SEARCHING

An inventor may wish to obtain an assessment of the patentability of their invention prior to incurring the additional drafting and filing expenses discussed herein. Patents from all countries are relevant to the patentability of an idea in Canada (and elsewhere) and while a search of Canadian and U.S. patents is not exhaustive, it typically does provide a good idea of the state of the prior art as it relates to the proposed invention at a reasonable expense. In addition this search can locate and provide copies of prior art which is required for the drafting of the patent application. Patents and patent applications which are disclosed by their inventors in turn provide a great deal of useful technical information to those interested in searching patents for such information.

There are numerous advantages to doing a comprehensive patentability search before proceeding to draft and file a patent application. These include the ability to fine‑tune your own patent application based on problematic pieces of prior art revealed in the search to avoid Patent Office rejections based on those at a later date.

WONDERING IF YOUR INVENTION IS PATENTABLE? We can help.

Patent filing process

The patent filing process begins once relevant searches have been carried out and the patent strategy has been determined.

GENERAL PROCESS

A patent application in its entirety needs to describe the invention in sufficient detail to be understood by a person with ordinary skill in the technical field to which the invention relates (this fictitious person is nominally referred to as a ‘person skilled in the art’). The claims define the scope of your patent. The remainder of the document needs to substantiate the scope and contents of the claims – anything which is claimed but not explained or enabled in the remainder of the patent application is not covered by the claims. It is the claims of your patent which are interpreted by a court in any infringement action.

In most countries, the first person to file a patent application for a particular idea is the individual entitled to patent protection, versus the first to invent.

EXAMINATION OF APPLICATION

Once a patent application is filed, the next stage in the patent filing process is examination by the Patent Office in each jurisdiction in which it has been filed. In Canada it is necessary to specifically request the commencement of examination of the application, which can be done at any time up for up to five years after the date of filing of the application. It is important to recognize that patent applications are not simply approved as filed – at issue is the grant of an important monopoly right which can be legally enforced against others to exclude them from making, using or selling the patented invention. Applications are therefore subject to careful scrutiny by the Patent Office, who may reject an application on numerous grounds.

Examiners in each Patent Office will review the claims and disclosure to ensure that claim is only made to subject matter to which you are entitled, and that various formalities are met. Additionally, the Examiner assigned to the case, who will be a person skilled in the technical field of the invention, will conduct a search of patent and non-patent literature to see what if anything similar has been done previously in the field. It is entirely possible that the Examiner will then object to the contents of the claims or the patent application on the basis that the invention is not sufficiently different from the prior art to be entitled to patent protection. Exchanges between an applicant/agent and the Patent Office will occur at this stage, the applicant/agent making arguments and effecting changes or amendments as necessary to satisfy the Patent Office. If the Patent Office should reject some or all of your application, there are usually avenues of appeal available as well. You should work closely with your lawyer or agent in the drafting and review of your patent application and throughout the patent filing process, as you know best just what the scope of your idea is and what it includes.

In some countries, the substantive examination of the patent application will be conducted automatically by the patent office in question in due course. In other countries, it is necessary to pay additional fees and to initiate a request for the commencement of substantive examination of a patent application before the document will be examined by a Examiner in the patent office in question. In the United States for example, examination of patent applications will take place in sequence automatically following the filing of the application.

In Canada it is necessary to request the commencement of examination of the patent application before the Canadian Intellectual Property Office and to pay an additional fee for that to take place. The request for examination before the Canadian office can be deferred for up to five years from the date of filing of the patent application. Practically speaking with this means is that an applicant can, once they get their application on file, simply let their application lie for a while if additional time is required to focus on other commercial aspects of their project. Other commercial reasons why examination might be deferred may be to further deferred the incurrence of additional significant costs in the examination process, or to stretch out to the greatest degree possible the length of the “patent pending” period if it is anticipated that there will be difficulties in obtaining an allowance of the patent application.

CONFIDENTIALITY PERIOD

In Canada, the United States and most other countries, there is an 18 month confidentiality timeframe following the filing of a first patent application, within which the contents of the patent application will not be available to the public. As such, following the filing of either a provisional/incomplete or a complete patent application, patent applicant can enjoy up to 18 months of secrecy around the contents of their patent application if they wish to do so.

International patent protection

A patent only protects your invention in the country in which it is granted, so it is necessary to seek international patent protection if you want your invention to be protected in other jurisdictions. If you have a Canadian patent you are protected from others building or using your invention within Canada, as well as outside of Canada and shipping or selling it into Canada. The only exception to the need to file in each country is the situation where a regional patent convention or treaty allowing for regional processing of patent applications is in place, such as in Europe.

In certain cases where a regional patent convention or processing system is in place it is still possible to file patent applications at the national level only in countries of interest. The benefit to this is that the costs are likely less where only very few countries are of commercial interest. There are also other potential strategic advantages in certain cases, such as where an application is filed for which it is anticipated that there will be difficulties in obtaining allowance of the patent application from patent authorities on the basis of prior art in the field – it may be desired to have the maximum number of attempts available to make such arguments. This is an issue for further consideration later in the process, but for the beginning consideration, it is worthy to note that single country filings, such as in individual countries in Europe, may reduce the overall costs of obtaining patent protection if there are only few countries of interest within a list of nations signatory to a regional patent convention.

COMPLETE PATENT APPLICATIONS

The simplest, most straightforward route of filing a patent application is to simply draft and file a completed patent specification for submission and handling at the Patent Office. The completed patent application, as can be presumed from the way that we refer to it here, is a complete document which is freestanding and can eventually be examined on its merits to assess patentability and potential issuance as a patent to the applicant or owner.

Primary benefits to proceeding by way of the filing of a completed patent application as the initiating document are simply that in the longer term the process will be the most cost efficient, and there will be fewer delays in the timeframe from the date of filing of the application to the hopeful date of issuance of a patent based on the document. Disadvantages to the complete route, versus starting with a provisional application which is outlined in further detail below, include the fact that there is at a cost to the filing of a completed patent application is the document of first instance, as well as the fact that if the research or the conceptualization of the invention is not yet quite completed there may be a modestly greater degree of flexibility available in a provisional application in terms of revisiting the subject matter of the document at a later date to come back and complete that rather than having to commit to claim language and the remainder of the document at this earlier stage in the process.

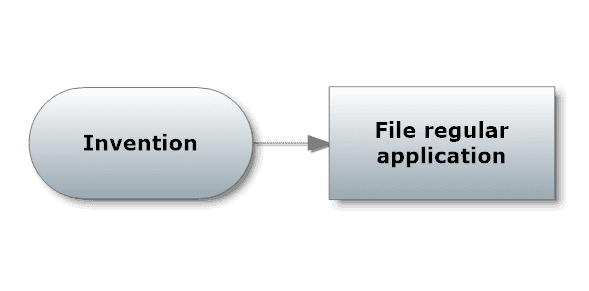

To provide a visual representation of the most basic filing of a regular patent application in Canada:

Figure 1: Filing completed patent application, no prior disclosure

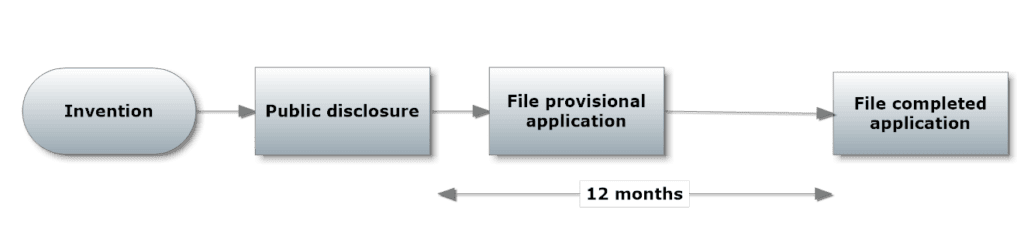

If there is already a public disclosure of the invention in play, such that the 12 month public disclosure grace period is being monitored or applied to the timeframe in question, the following figure is intended to demonstrate how the public disclosure of the invention in advance of the filing of a patent application will affect the timing of the filing of a completed application – in Canada no more than 12 months from the date of the first enabling public disclosure:

Figure 2: Filing completed patent application, invention previously disclosed

PROVISIONAL/INCOMPLETE APPLICATIONS

The second filing route which is available to a patent applicant is to proceed by way of filing what is referred to as a “provisional” or “incomplete” patent application. This type of application is available in both Canada and the United States. Effectively what is permitted by the provisional route is for a patent applicant to provide a somewhat incomplete invention disclosure to the patent office, and to secure for a limited period of time of filing date upon which a completed application can later be based. An early patent filing date can be obtained and it is possible to defer, either for economical or for subject matter reasons, the commitment to the final content of the patent specification for up to 12 months. Procedurally what is done then with a provisional application is that within the 12 month period the applicant needs to file a completed application, claiming priority back to the provisional filing date.

The following chart is intended to demonstrate the basic timeline of filing a provisional patent application, in a circumstance where there is no previous public disclosure at play in advance of the date of filing. A public disclosure can take place following the filing date of the provisional application without an effect on the completion timeline:

Figure 3: Filing provisional application, subsequent completion, no prior disclosure

The following chart shows the adjustment to the timeline and requirements in a provisional to complete filing strategy, where the subject matter of the invention has been disclosed to the public in advance of the filing of the provisional patent application:

Figure 4: filing provisional application, subsequent completion, invention disclosed in advance of filing

To summarize then, the primary benefit of the provisional or incomplete patent application filing route is that it does allow us to more quickly and at a lesser cost upfront get something on file to secure a patent pending filing date and protect the client in respect of a following or anticipated subsequent disclosure. Sometimes the provisional route is also found desirable from the perspective of being able to file a larger number of applications upfront, a provisional basis, to initially throw the net as widely as possible in the patent portfolio, and then potentially abandonment or others to proceed as the completion deadline for the provisional applications approaches and the research and development in respect of the technology may be further along, or even the marketing strategy or the market development on the technology may be further along so that either geographically there is a greater appreciation where the market is in terms of developing the remainder of the patent portfolio, or even just understanding where the particular hotspots are in terms of the proposed patent protection.

INTERNATIONAL FILING STRATEGY

Determination of a strategy around international patent protection requires the consideration of multiple layers of statutory requirements at the national and international level. However, the basic options in terms of an international filing strategy include one or more of the following options:

- Filing national or regional patent applications in countries of interest directly;

- Filing national patent applications in countries of interest pursuant to the Paris Convention within 12 months of a first filing date within a Convention country;

- Filing an application pursuant to the Patent Cooperation Treaty, which will mature into national patent applications in countries of interest.

National Applications

The first option to consider in terms of a strategy around international patent protection is to simply consider filing the patent application nationally in the patent office of each country of interest. This is the most straight-forward process.

PARIS CONVENTION

Under the International Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, the contracting parties, including Canada, formed themselves into a union, known as the Paris Union, for the protection of industrial property including patents. This agreement is known as the ‘Paris Convention’. The basis of the Paris Convention is equal treatment of the nationals and residents of the member countries, known as the Convention countries; thus applications for the grant of patents made by those who are applicants in Convention countries within one year of the first application for a patent are entitled to priority from the date of the application abroad. Such priority does not affect the duration of the term of the patent.

As long as a patent application is filed within one Convention country in advance of public disclosure, applications can be filed in other Convention countries within 12 months claiming priority and the benefit of the original filing date. This gives an applicant an ability to stagger their international filing costs, either following public disclosure of an invention or in a case where that first 12 months grace period is sufficient to further refine the listing of countries within which an applicant would like to apply for patent coverage (again, so long as those countries are signatories of the Convention).

Patent applications filed in foreign countries pursuant to the Paris Convention are national applications and are each handled individually. The timeline for completion is therefore shorter than some other international filing methods such as the PCT, but the foreign costs are incurred earlier in the process.

The following figure is intended to demonstrate a circumstance in which it is desired to file additional applications outside of Canada in respect of an invention, where the initiating document was a provisional application, and there was no previous public disclosure of the invention in advance of filing of the Canadian incomplete document:

Figure 5: Paris Conv. international patent filings, start w Canadian incomplete

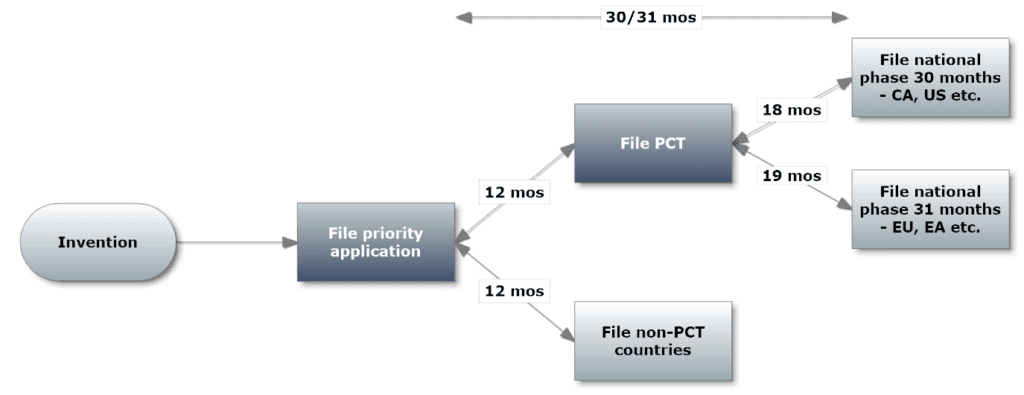

INTERNATIONAL PATENT PROTECTION THROUGH THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT)

A mechanism by which international patent protection can be significantly streamlined is the Patent Cooperation Treaty. Effective January 2, 1990, Canada satisfied Parts I and II of the Patent Cooperation Treaty done at Washington on June 9, 1970, commonly called PCT, thereby joining a system whereby one form of application for a patent may be filed in a receiving office, giving the applicant an option of having that application deemed to have been also filed in such other member countries as the applicant may elect. The PCT allows an applicant to file a single application which will effectively secure a filing date in all countries who are signatories to the PCT by making a single filing. The PCT does not provide an international or global patent mechanism but provides for streamlining to some extent the international filing process. A PCT application must eventually be converted into a national application in each country in which it is desired to perfect patent protection.

The PCT process is divided into 2 stages – the international phase and the national phase. The international phase is the first stage, in which the international application is filed, designating all of the countries in which protection is potentially desired. The international stage filing effectively secures the filing date in all designated countries, and then allows the applicant to postpone the commencement of actual national proceedings in the countries of interest by 30 months from the earliest priority date claimed.

Some of the advantages of the PCT process are the following:

- An international search is performed and the results provided to the applicant, which gives us a chance to anticipate the search results in individual countries;

- The deadline to file national applications is extended by either 18 additional months to 30 months from the earliest priority date claimed;

- An international examination can be requested which will again allow the applicant to get some preliminary feedback on the application in advance of the national filings, which can allow for a greater latitude to correct defects in the application in advance of national filing costs being incurred.

Another alternative is to file the PCT application as the originating priority application, rather than claiming priority from a national application. The following diagram demonstrates this approach:

Want to protect your idea internationally or fine-tune your strategy around international patent protection? Let us know and we can help.

Patent infringement & enforcement

Once you have spent the time and the money to obtain a patent registration, you then have a statutory monopoly which you can endeavor to enforce against competitors in cases of patent infringement. Enforcing the rights that are guaranteed by your patent is your responsibility – while the patent office authorizes or grants to you the monopoly to your invention, it is the responsibility of the patent owner to police and enforce their own patent rights.

Typically the patent is enforced by way perhaps first of a cease-and-desist strategy followed with the issuance of legal proceedings if necessary. In the Canadian context, proceedings for patent infringement can be undertaken either in the Federal Court or in the superior courts of the provinces. There are limitations and strategic differences to commencing an enforcement proceeding in either of those courts.

A patent enforcement lawsuit is typically a civil lawsuit, although some countries do have criminal penalties for some types of patent infringement or other patent related activities. Typically the damages or remedies which might be sought and rewarded in a patent infringement lawsuit would include monetary compensation for past infringement and/or an injunction which would prohibit the defendant from engaging in future acts of infringement.

The claims of a patent are what clearly and distinctly state the rights that a patent owner has claimed as their invention, and which the Patent Office has recognized and granted. The claims of the patent are what define the scope of the monopoly right granted under the patent, with the remainder of the document being intended to support the construction, interpretation or understanding of the claims. Any approach to patent infringement is effectively a two-stage analysis – firstly the issue of infringement must be determined, and then the issue of the validity of any parts of the patent which are potentially infringed must be addressed.

Often the defense which is put forth by an accused infringer of the patent is to challenge the validity of the patent on various grounds. A patent can be invalidated on grounds that vary from country to country but typically they are a subset of the patentability requirements for that country. Most often the primary grounds for invalidating a patent would be statute barred subject matter based on a prior publication by the inventor or a related party, availability of published prior art in the jurisdiction or elsewhere in the world that renders the invention obvious at the relevant time, or a failure to mention all of the inventors etc.

In many cases the commencement of a patent infringement lawsuit comes as the culmination of a great amount of strategic planning and foresight by the patent holder. There are often many different strategies which can be contemplated, either contentious they are amicably, to accomplish the objectives of the patent holder. Patent enforcement strategy is just one of the weapons we have at our disposal in the development of full sum intellectual property plans and strategies on behalf of clients.

CONTACT US to learn more about how you can protect yourself against potential infringers.